Summary

How claims of action differ

Most reasoning claim types (fact, cause and effect, definition and classification, interpretation, evaluation) describe or assess reality. In contrast, claims of action aim to change reality.

So, while the other claim types require a judgment about the adequacy of the reasoning and evidence provided, claims of action must also be judged by whether they achieve the desired real-world results.

Limits of existing frameworks

Existing frameworks that incorporate the need to assess progress and course correct like John Boyd’s OODA loop and W. Edwards Deming’s PDCA cycle were designed for different contexts. They don’t capture the full complexity of claims of action, such as the dependence on other claim types for support, the need to sustain motivation and the importance of defining the desired future state.

Introducing the Teleopraxis model

Teleopraxis can be defined as “the taking of purposeful action to close the gap between an entity’s current state and its desired future state”. The Teleopraxis model provides a structured framework for guiding change for individuals, organisations, and societies.

The six key pillars of the Teleopraxis model:

- Desired future state – change requires clarity about goals and the criteria used for judging success.

- Using feedback – evidence of results must be gathered and used to refine future actions.

- Multiple iterative cycles – progress unfolds through repeating loops of assessing, deciding, acting, and monitoring.

- Correcting errors – gaps between results and goals should be treated as opportunities for learning and course correction.

- Sustaining motivation – emotional commitment is essential in order to continue through setbacks and challenges.

- Role of the different claim types – different argument claims are being made and assessed through all parts of the decision-making process.

Simplified version of the Teleopraxis model

The simplified version is based on four repeating steps: assess progress, decide and plan, act, and monitor results. These continue until the desired state is achieved or abandoned.

Introduction

My argument claim hexagon model identifies the six different types of claim. Five of them — fact, cause and effect, definition and classification, interpretation, and evaluation — aim to describe or assess reality. The sixth, claims of action, aim to change it.

This difference is important. A claim of fact can be tested against evidence; a claim of cause and effect against whether one event really results in another; and a claim of interpretation against whether the assigned meaning makes the best sense of the evidence.

In contrast, a claim of action is judged on whether it achieves the desired results in the real world.

Frameworks such as John Boyd’s OODA loop (Observe–Orient–Decide–Act) and W. Edwards Deming’s PDCA cycle (Plan–Do–Check–Act) already acknowledge that effective action requires iteration. Yet the OODA loop was designed for military conflict and the PDCA cycle for quality improvement in industrial systems.

Neither captures the full complexity of claims of action: the reliance on other claim types for support, the importance of sustaining motivation and the importance of defining the desired future state.

That’s why I developed the Teleopraxis model. It is designed to guide purposeful change across a wide range of domains (from individuals and organisations to countries and societies) using a process of reasoning, assessing results and refining actions.

How claims of action differ from the other five types of claim

In my argument claim hexagon model, I suggest that claims can be divided into six types:

- fact – what is true or false?

- cause and effect – what causes what?

- definition and classification – how should something be defined or classified?

- interpretation – how should something be understood?

- evaluation – is something good or bad?

- action – what should be done?

There are two main reasons why claims of action differ from the other types of claim.

1. Claims of action are more complex than any of the other claims. That’s because they normally include all of the other types of claim. In contrast, the other types of claim will have a more limited number of supporting claim types and, indeed, claims of fact can exist on their own.

Take the hypothetical example of an action claim dealing with policy to tackle childhood obesity.

The claim of action might be something like “Schools should implement a daily 30-minute structured physical activity program for all students to combat rising childhood obesity and improve long-term health outcomes”.

This claim can only be justified by using the other types of claim to support it:

- fact: childhood obesity rates have tripled in many countries over the past 40 years

- cause and effect: a lack of physical activity, combined with high-calorie diets, directly contributes to weight gain and increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease later in life

- definition and classification: structured physical activity refers to guided exercise sessions, such as aerobics, sports drills or dance, which can be contrasted with unstructured free play

- interpretation: the steady rise in childhood obesity despite nutrition awareness campaigns suggests that information alone is insufficient and that behavioural routines embedded in the school day are necessary

- evaluation: childhood obesity should be considered undesirable as it interferes with stamina and energy levels and also has a negative impact on longer-term health outcomes.

Of course, the nature of argument and a commitment to finding a solution that works means that anyone can disagree with the main claim or any of the supporting claims by providing challenges to the evidence or reasoning provided.

2. There is a qualitative difference between claims of action and the other types of claim. The claims made by the first five claim types involve understanding or assessing reality (eg, “This is true,” “This caused that,” or “This is good/bad”).

In contrast, claims of action are about changing reality. Their purpose is to initiate purposeful change by specifying what should be done and how this should be done.

This difference becomes more apparent when one considers how changes to the different claim types occur.

Revisions to the first five claim types happen in response to new information and arguments which, if accepted, lead to a new or refined assertion about reality.

Whereas claims of action are revised through an evaluation of progress and resulting decisions adjusting goals and strategies.

The need for a decision-making model

Claims of action therefore require not just an assessment of the adequacy of the evidence and reasoning provided but also an ongoing decision-making process that assesses progress and makes course corrections where necessary.

I’ve developed a model to do this, which I’ve called the Teleopraxis model.

The word ‘teleopraxis’ is made up of two parts:

- ‘Teleo-‘ comes from the Greek word ‘telos’, meaning ‘end, purpose or goal’

- ‘Praxis’ in Greek means ‘action, practice, or deed’.

Teleopraxis can be defined as “the taking of purposeful action to close the gap between an entity’s current state and its desired future state”. Entities can include individuals, businesses, organisations and countries.

The model has six key pillars:

- being clear about the desired future state

- using feedback

- understanding the need for multiple iterative cycles

- correcting errors

- sustaining motivation

- understanding the role of the different argument claim types in the decision-making process.

1. Desired future state. Having clarity about the desired future state is critical for two reasons:

- effective strategies can only be designed with a clear idea of the destination

- clarity is necessary to be able to assess the progress being made.

2. Using feedback. It’s vital to collect information about the positive or negative results being achieved so that this can then be used to improve the effectiveness of future actions.

3. Multiple iterative cycles. A cycle involves:

- assessing overall progress towards the desired state

- deciding what needs to be done to make further progress

- planning how best to do it

- putting the plans into action

- monitoring the results of those actions.

Sometimes goals can be achieved in one cycle. However most complex goals will require multiple cycles.

The nature of iteration allows the making of course corrections to get closer to the desired state.

These cycles will continue until the desired state is either reached or is no longer considered to be a priority for the learner.

4. Correcting errors. Drawing on David Deutsch’s insight that knowledge advances by identifying and eliminating mistakes, the model makes error correction one of its key pillars. Each cycle of action provides feedback to show gaps between the actual results and the desired results. By treating these gaps as opportunities for learning instead of failures, plans for the next cycle can be corrected and improved.

5. Sustaining motivation. Achieving change is not just a process of reasoning and action. It’s also an emotional journey. Without a strong sense of emotional commitment, even well-designed plans can stall as motivation fades and setbacks start to feel overwhelming. That’s why the model focuses on the need to sustain positive emotions, such as hope, determination and curiosity, and manage negative ones like frustration and anxiety.

6. Understanding the role of the argument claim types. Different claims are being made and assessed through all parts of the decision-making process. For example:

- the desired future state corresponds to a claim of evaluation: deciding on the desired state requires not just evaluational criteria but also the specific and observable evidence that will confirm whether or not the criteria have been met (“What do we want to achieve and how will we know when we’ve achieved it?”)

- feedback involves establishing claims of fact about the results achieved (“What happened as a result of our actions?”)

- the ability to correct errors depends on being able to establish cause and effect relationships (“Why didn’t our actions produce the results we wanted?”)

- maintaining motivation involves claims of evaluation (“Is this goal still worth pursuing?”) and claims of fact to prove that progress is being made.

A simplified version of the Teleopraxis process

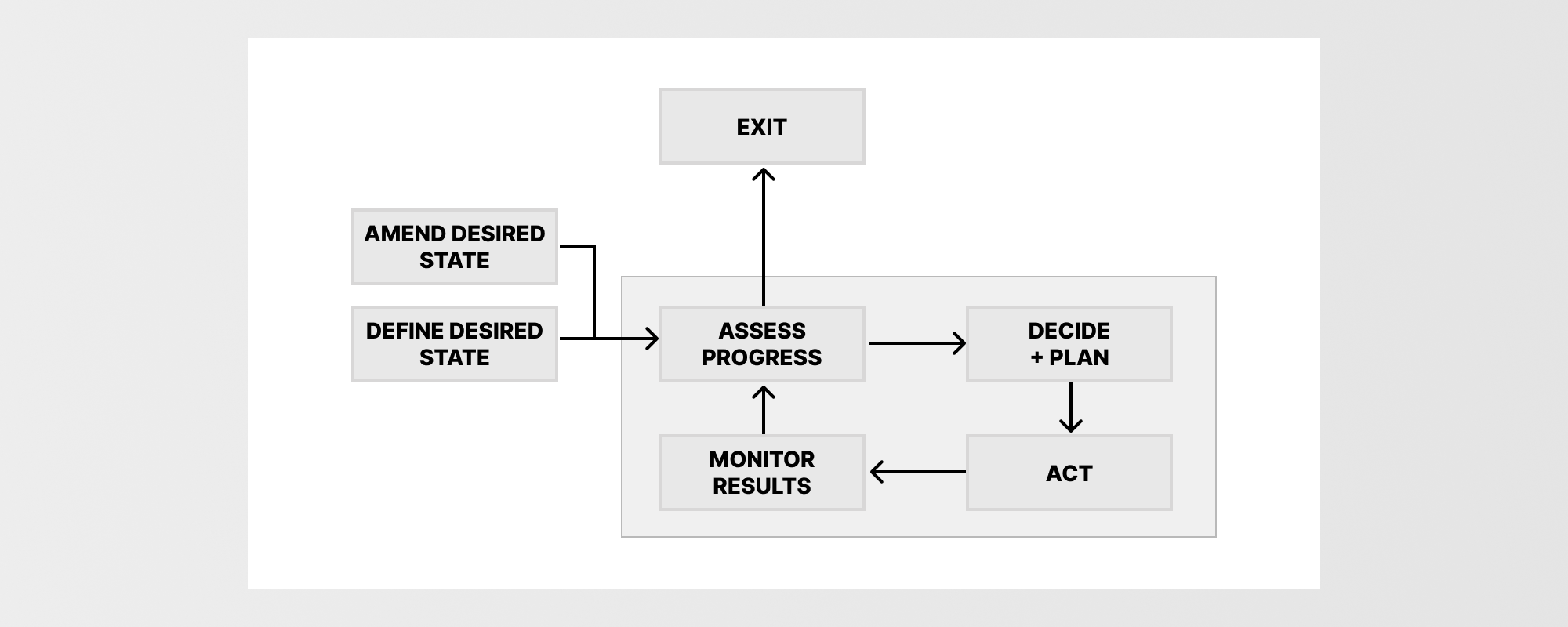

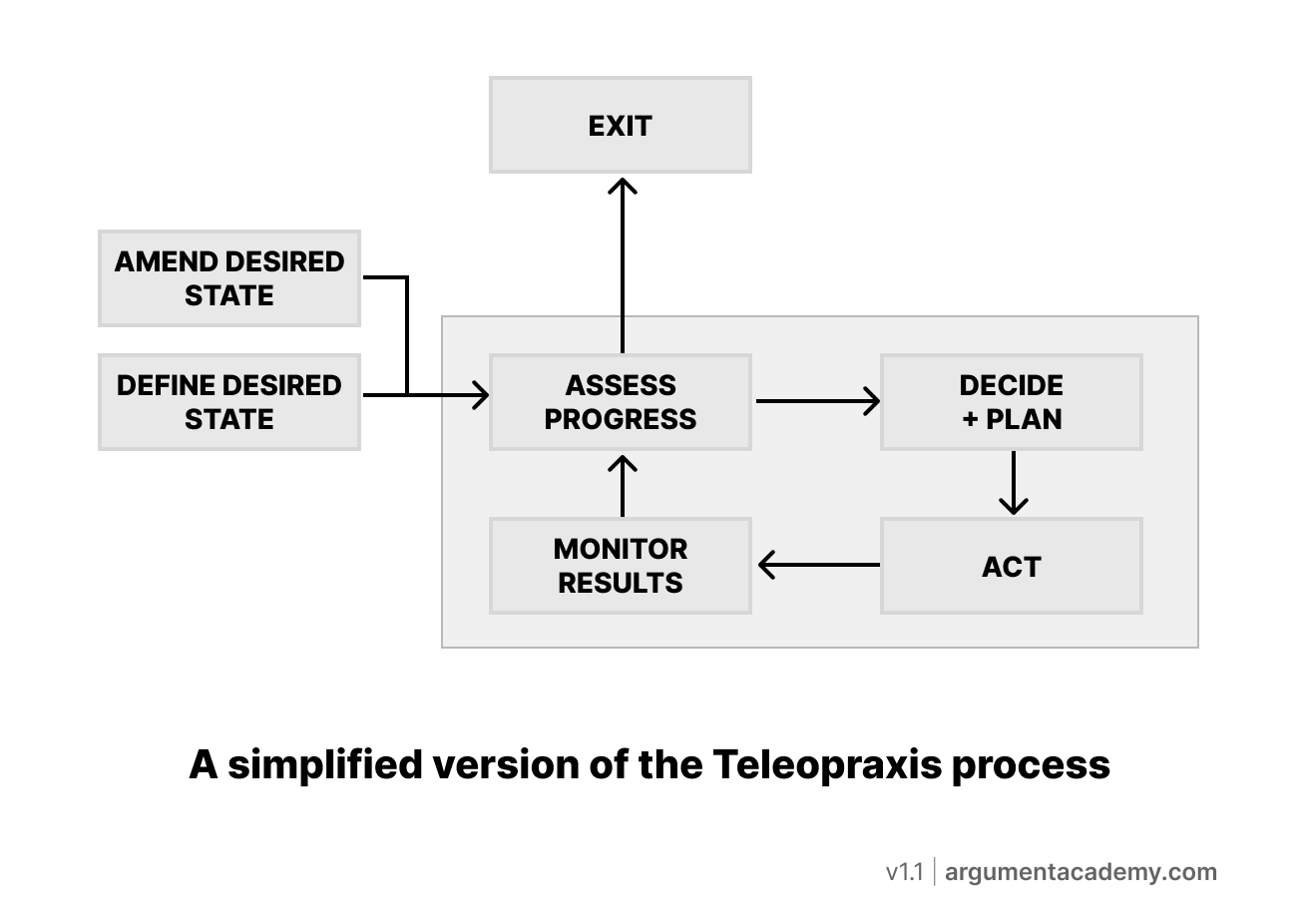

Below you can see a simplified version of the Teleopraxis process.

The core elements of a cycle are:

- Assess progress

- Decide + plan

- Act

- Monitor results.

The first cycle starts when a desired state is defined and a decision is taken to move towards that desired state. The sequence is then followed over multiple cycles until the overall process comes to an end.

Exiting the cycle can happen for various reasons, including:

- the desired state has been achieved

- there are not enough resources available to achieve the desired state (eg. time, energy, money)

- the desired state is no longer a priority

- achievement of the desired state no longer seems possible.

The essence of this process is time: the need to continue tweaking plans and actions until the desired state has been reached.

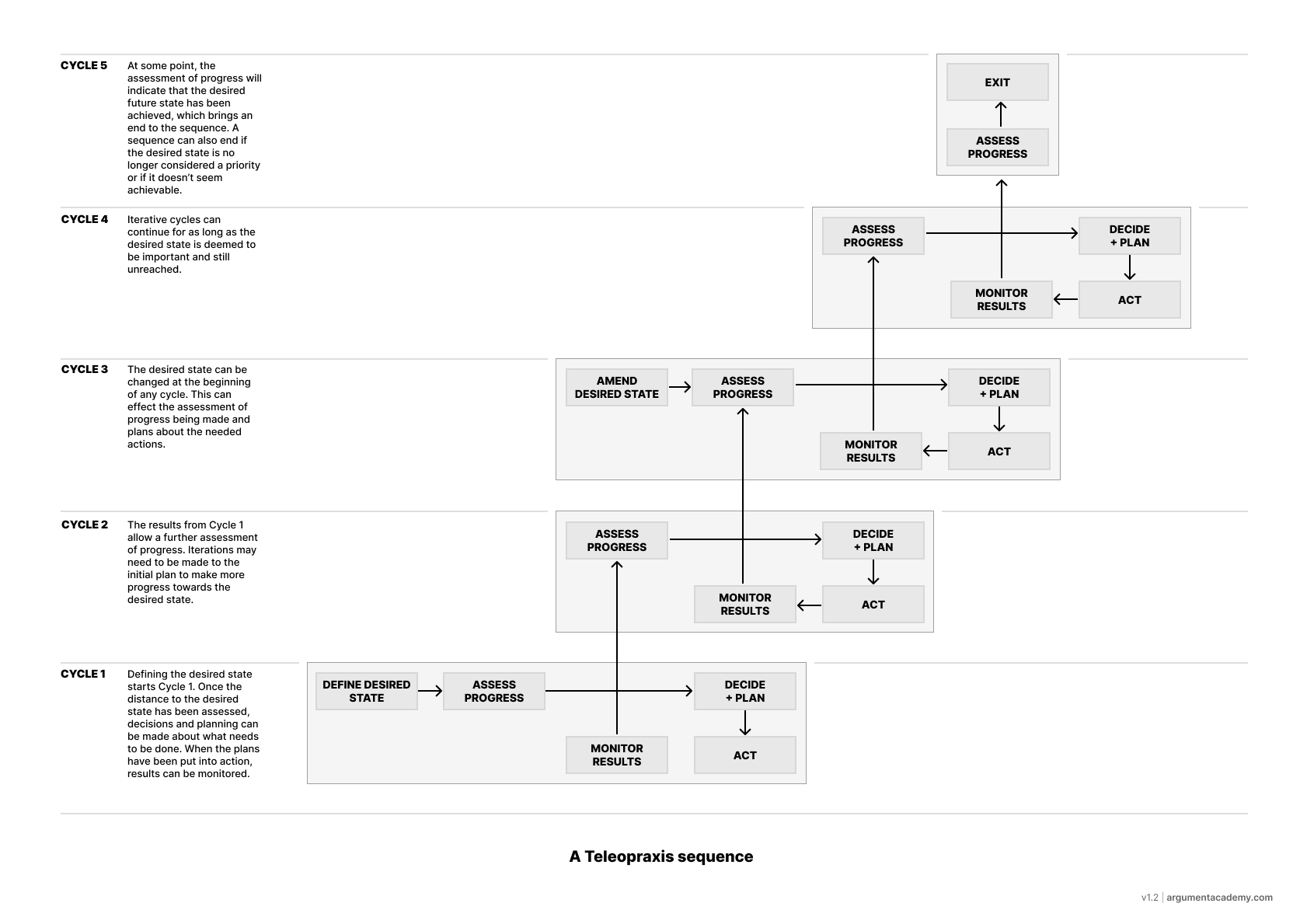

The diagram below shows how the process can be visualised over multiple cycles.

Conclusion

Claims of action differ from other argument claims because they seek to reshape reality rather than simply describe or assess it. They require not just sound reasoning but also cycles of feedback and adjustment.

The Teleopraxis model provides a framework for this process. By integrating all the six argument claim types, it offers a structured way to turn purposeful intentions into meaningful change.

Further articles

I’ll be writing further articles on the Teleopraxis model, including discussing practical uses for the model and explaining the detailed version of the model. Sign up to the newsletter so you can be informed when the articles appear.

Thanks

Thanks to @kevindmackay for providing feedback when I was developing the model and for making a very useful comment that helped me come up with the word ‘teleopraxis’ as a name for the model.