Summary

Arguments don’t run on facts alone. Beneath every claim lies a warrant, the hidden principle that makes evidence relevant. This article introduces Stephen Toulmin’s concept of warrants, explores how they arise from history, culture, and narrative, and shows how they shape debates in politics, public health, and marketing.

By examining controversies such as gun control and vaccination alongside consumer behaviour, it demonstrates that persuasion depends less on piling up data than on recognising and working with the warrants people already hold.

Introduction: Why warrants matter

I’ve always been intrigued by the structure of argument, whether it’s a politician pleading for votes or a friend arguing about a book they have just read.

Facts matter, but they’re not the whole story. Every argument rests on a warrant — the often unstated principle that ties the evidence to the conclusion.

In this article, I’ll explain Stephen Toulmin’s concept of warrants and show how they shape debates and strategies in politics, public health, and marketing.

By the end, I hope to persuade you of the power of warrants and how you can use that understanding in practice.

Stephen Toulmin’s concept of warrants

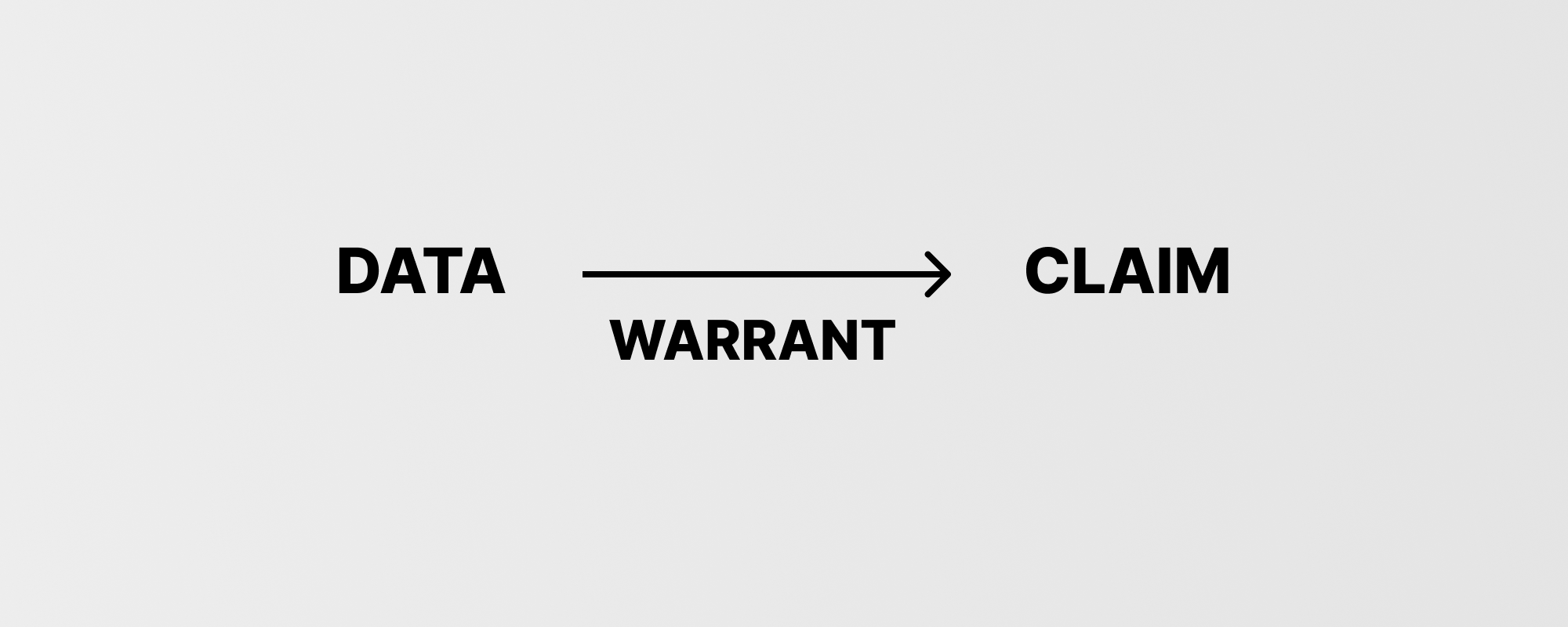

The concept of warrants was first introduced by philosopher Stephen Toulmin in his 1958 book The Uses of Argument. Toulmin showed that everyday arguments can’t be analysed as perfect logical proofs. Instead, they follow a looser structure: a claim is supported by data with both connected by a warrant:

- Claim: the conclusion being advanced (“This medicine is safe and effective”).

- Data: the evidence offered in support (“Because it was tested in clinical trials”)

- Warrant: the underlying principle that justifies why the data support the claim (“Clinical trials establish the safety and effectiveness of medicines”).

Unlike claims or data, warrants are often left implicit. But they are critical: if an audience rejects the warrant, they must reject the claim since the evidence is no longer accepted as relevant.

Taking the example above, if anyone refuses, for whatever reason, to accept the warrant that “clinical trials establish the safety and effectiveness of medicines”, then they will refuse to accept the claim that “this medicine is safe and effective” on the basis that “it was tested in clinical trials”.

Toulmin’s important insight was that persuasion does not just rely on discussion about the evidence but also about whether people accept the underlying principles that create the bridge linking the evidence to the claim.

How warrants arise: Lessons from research into public attitudes to genetic research

The power of warrants is shown in the 2005 paper Warranted concerns, warranted outlooks: A focus group study of public understandings of genetic researchby Bates, Lynch, Bevan, and Condit. 1

It’s one of my favourite papers. It gives the best description I’ve come across of how warrants get generated. It also shows how responses that don’t use scientific terminology can still be reasonable and well-founded, and it offers strategies for addressing specific warrants in arguments.

The research used focus groups with members of the American public to ask them about their attitudes to genetic research, including the potential risks and benefits.

The study found that participants’ attitudes toward genetic science were determined not just by scientific evidence but also by warrants that shaped how they interpreted that evidence.

The researchers identified several types of warrants held by the study participants including:

- pragmatic warrants: weighing benefits and risks (“If it cures diseases, it’s worth it”)

- precautionary warrants: uncertainty about consequences justifies caution (“Genetic science could become a threat to humanity”)

- value-based warrants: fairness, autonomy, justice, privacy (“It’s wrong if only the rich benefit”)

- definitional warrants: drawing boundaries what’s acceptable (eg. treatment) and what’s not (eg. biological enhancement) (“Treatment of disease is fine but creating designer goes too far“)

- authority warrants: trust or lack of trust in institutions and experts (“Corporations will unfairly exploit genetic testing because that’s what they do”)

- analogy warrants: metaphors and comparisons (“Genetic testing will become as ubiquitous in the workplace as drug testing is now”)

Here are some of the reasons participants used as sources for the warrants they held:

- observations of the workings of capitalism prompted the warrant that corporations would unfairly take advantage of genetic testing

- memories of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study led some African Americans in the study to question their ability to trust medical research

- Aldous Huxley’s novel Brave New World and the 1997 science fiction film Gattaca were both quoted as providing examples of the dangers of having societies divided by genetic hierarchy

- knowledge of existing exclusions in insurance policies led some to worry that coverage exclusions would be expanded when genetic testing was brought in.

I find it particularly interesting how novels and films can supply vivid narratives which end up functioning as warrant-generating devices.

The study shows that arguments are filtered through pre-existing warrants rooted in personal experiences, history and culture. If these warrants aren’t directly addressed, persuasive efforts can fail.

The use of warrants in arguments

With this background, let’s now explore how warrants shape arguments in three domains: politics, public health, and marketing.

The examples I have chosen to illustrate politics and public health – gun control and vaccination – are both controversial and divisive. I’m not trying to produce the final word on either. Instead I’m hoping to show how using the lens of warrants allows a different approach to discussing these issues.

The third example, marketing, is very different to the other two. I’ve included it here to show the versatility of warrant analysis.

Warrants in politics: The need to go beyond the evidence

Political debate obviously involves discussions about evidence. But just as important is the need to look at the warrants being used.

Take the case of gun control in the United States. Those in favour of gun control might argue the following:

- Claim: “We should restrict access to assault weapons”

- Data: Countries with stricter gun laws have lower rates of gun deaths

- Warrant: “Government should limit individual freedoms when they endanger public safety”.

Opponents may accept the data that gun deaths are higher in the U.S but can still reject that warrant in this context.

Their position rests on an opposing warrant: “The right to bear arms is a fundamental freedom that must not be infringed”.

Each side bases their warrants on different sources. Gun control supports draw on the experience of mass shootings and the success of successful regulation abroad. Opponents draw on the Second Amendment, narratives of self-reliance, and hypothetical scenarios like resisting an oppressive government.

These competing narratives generate vastly different opinions about what needs to be done.

Warrants in public health: Why people against vaccination are unmoved by attempts to persuade them

In public health, persuasion might seem straightforward: present evidence from clinical trials and people will follow the recommendation. But vaccine resistance shows that persuasion fails when warrants lead people to question the actual data.

Public health relies on warrants such as:

- “Treatments proven in clinical trials should be adopted”

- “Recommendations from medical authorities are trustworthy”

- “Individuals have a duty to participate in vaccination to protect the community”.

However these are often rejected by people who oppose vaccinations. A commonly-held warrant questioning the trustworthiness of institutions (‘”Scientific authorities and pharmaceutical companies are corrupt”) may lead them to disbelieve the accuracy of the data itself.

Past medical failures and narratives about conspiracies supply a ready-made warrant: “Authorities that have lied before cannot be trusted now“.

And anyone holding that warrant will not find messages from the authorities to be persuasive.

Warrants in marketing: Matching messages to buyer needs

Marketing messages list features and benefits, but their persuasiveness depends on whether those features connect with the buyer’s warrants.

Different customers operate with different warrants:

- Luxury buyers: “Products that are expensive and prestigious increase my status”

- Budget-conscious buyers: “Affordable and functional products are a sensible choice”

- Eco-conscious buyers: “It’s important to buy products that are environmentally sustainable”.

Persuasion fails when the marketer assumes the wrong warrant. For example, a company which stresses technical superiority (“better engineering means higher value“) may fail to win customers who care most about simplicity (“ease of use matters more than complexity“).

Strategies: Working with warrants in practice

This section starts with an examination of the recommendations from the Bates et al paper. I then move on to look at how individual warrants can be addressed in the gun control and vaccination debates, and in marketing.

Recommendations from the Bates paper

Bates and colleagues concluded with simple but powerful recommendations for genetic researchers, which are relevant to anyone involved in persuading others.

They write:

“Advocates of genetic research may want to allow public understanding to shape the arguments that they make. Should genetic researchers and allies treat their public as interlocutors instead of as students who need facts, these researchers may find that their work becomes more acceptable to the public.”

This, they suggest, can be done in two ways:

1. Develop new policies and actions that directly address particular concerns:

“The public is able to articulate good reasons for being concerned about the implications of genetics. As such, geneticists and allied researchers may wish to take action to address these concerns and report on these actions. For example, geneticists could enforce a strict code of ethics that forbids the exploitation of genetic samples without the patient’s permission. Medical practitioners can show how they physically and electronically secure medical records so that insurers and employers cannot use the results of genetic tests to discriminate. Researchers who find different response rates between European Americans and African Americans to particular medications can discuss their results more carefully so that racist interpretations of the findings become more difficult.”

2. Present reputable and believable counter-evidence that may start to weaken the grip of particular warrants:

“If everyday experience is used as a warrant for thinking about genetic medicine, the data of bad interactions with medical providers cited by our participants could be rebutted with positive personal experiences. When analogies to popular culture, such as Gattaca, are cited as reasons to fear developments, analogies to the future offered by Star Trek may be useful for arguing through the same logic. If historical analogies are used, each instance where a Tuskegee Study is recalled can be answered with references to Salk’s work on polio.”

Their suggestion to treat people as equals who should be listened to and have their concerns understood has to be the start of any effective persuasion process.

Politics: Working with warrants in the gun control debate

There is no easy answer to the gun control debate because of the conflicting nature of each side’s warrants. One side appeals to public safety, the other to constitutional rights. On the face of it, these are impossible to reconcile.

A possible first step might be for both sides to identify and articulate their opponents’ warrants.

A gun control advocate might say: “I understand that the right to bear arms represents the importance of self-reliance and constitutional tradition to you”. A gun rights supporter might reply: “I see that your priority is keeping schools and public spaces safe from mass shootings”.

Naming and recognising these warrants won’t eliminate disagreement. However it does shift the conversation by starting with an acknowledgement of the positive intentions of the other side.

From there, further small steps may be possible. Higher-level shared warrants, such as protecting families and valuing responsible citizenship, could provide common ground for compromise measures like, for example, restrictions on specific classes of weapons, even while deeper disagreements remain.

If one side treats the other side’s principles as illegitimate, then compromise becomes impossible. And that deepens the sense of political polarisation.

History shows that, when no shared warrants remain, disputes risk sliding towards civil conflict. Understanding your opponents and their warrants better is therefore not just a matter of civility. It is an insurance against political discourse breaking down altogether.

Public health: Working with warrants in the vaccination debate

The vaccine debate differs from the gun control debate in a critical way. With gun control, both sides typically agree on the facts. However, what they disagree about are the warrants that link those facts to the conclusions drawn.

With vaccination, however, the warrants about the factual safety of vaccines themselves are disputed. People against vaccination often claim that clinical trials are flawed, manipulated or untrustworthy. That means that they reject outright basic warrants that connect evidence to conclusions, such as “Trials which show that a treatment is safe and effective can be trusted”.

This makes the debate unusually intractable because persuasion collapses at the most fundamental level of argument. If one side refuses to accept the warrant which defines what counts as reliable evidence, then no new data, however robust, can settle the dispute.

One possible step forward would be to ask: “What kind of clinical trial design would people against vaccination accept as trustworthy?”. An acceptable design might include greater independence from government and pharmaceutical companies, open access to raw data or extremely long-term follow-up studies.

The lesson here is that, when factual warrants collapse, debate becomes almost impossible because what counts as evidence is contested.

Marketing: Working with warrants using Jobs to Be Done theory

Customer research can be viewed as uncovering the hidden warrants behind buying decisions.

Let’s look at this through the lens of Jobs to be Done (JTBD) theory, which is a popular tool for customer research.

JTBD theory suggests that customers ‘hire’ a product or service to get a particular job done in their lives (e.g. “become more knowledgeable“, “display my sophistication“, “help me feel in control of my finances“). Those jobs are not just about the functional task the product helps with but also the resulting emotional and social benefits that the product delivers.

From the perspective of reasoning, these jobs can be seen as warrants in disguise. A customer is persuaded not just by a product’s features but also by the underlying justification:

- Claim: “I should buy this product”

- Data: “It is cheaper, faster or better designed”

- Warrant: “Products are worth buying when they help me accomplish the jobs I care about“.

JTBD interviews and analysis aim to surface a buyer’s underlying warrants, which can be defined as the principles or assumptions that make the features relevant to the buyer’s situation.

If marketers fail to understand the jobs the customer is hiring the product for, they can assume the wrong warrant which means that their messaging will then miss the mark. A software company that stresses “powerful features” may fail if the buyer’s real job is “reduce complexity so I can focus on strategy”.

By contrast, when marketers understand the deeper reasons which allow a buyer to feel justified in buying their product, they can align their message with their buyer’s warrants. As a result, their marketing materials will become far more effective.

Conclusion: The potential of warrants

Warrants are powerful but little discussed, possibly because they are not easy to grasp.

Yet they are a valuable addition to anyone’s analytical toolbox. Not only do they allow you to understand the deep structure of an argument someone is making to you. They also allow you to respond not just with respect but also with options that may actually help to change their mind.

- Warranted concerns, warranted outlooks: A focus group study of public understandings of genetic research. Benjamin R. Bates, John A. Lynch, Jennifer L. Bevan, Celeste M. Condit. Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 60, Issue 2, January 2005, pp. 331-344. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.012. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15522489[↩]